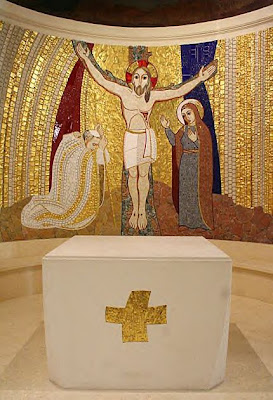

This kind of art has been defined very beautifully by the Catechism of the Catholic Church:

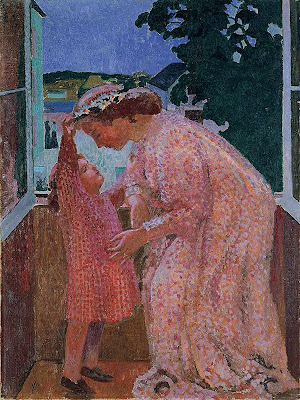

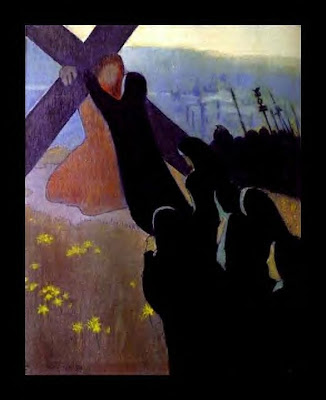

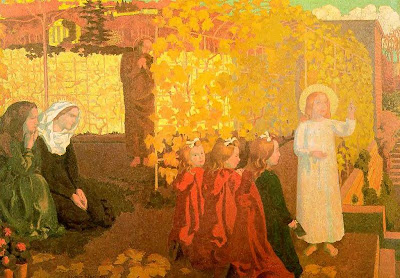

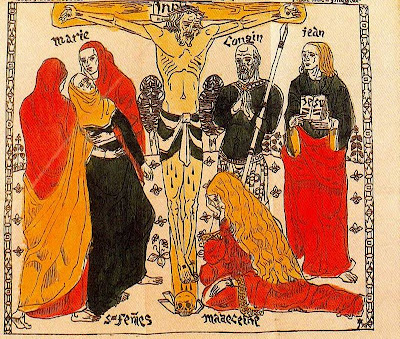

`Sacred art is true and beautiful when its form corresponds to its particular vocation: evoking and glorifying, in faith and adoration, the transcendent mystery of God—the surpassing invisible beauty of truth and love visible in Christ, who 'reflects the glory of God and bears the very stamp of his nature' (cf. Heb 1:3), in whom 'the whole fullness of deity dwells bodily' (cf. Col 2:9). This spiritual beauty of God is reflected in the most holy Virgin Mother of God, the angels, and saints. Genuine sacred art draws man to adoration, to prayer, and to the love of God, Creator and Savior, the Holy One and Sanctifier. [24]`

In other cases, the ordering of the art to the glory of God is the end of the artist, the finis operantis. In other words, his motive is to glorify God, even though the work of art itself is not destined for the beautification of church and liturgy. This is religious art, art shaped and pervaded by faith and prayer. Examples here would be the painting of Rouault, the music of Messiaen, and the poetry of St John of the Cross, George Herbert, and Gerard Manley Hopkins.

The great French Catholic poet and dramatist Paul Claudel argued that great art, even when it is not explicitly religious, can achieve good spiritual effects in others, if not in the artist himself. He gives as an example the poetry of Rimbaud. Its haunting beauty, its sense of eternity and the transcendent mystery of human life, helped to liberate Claudel from the positivistic scepticism of his youth—the sickening servile worship of science to be found in Ernest Renan.

`I shall always remember that morning in June 1886 when I bought the little copy of Vogue containing the first part of Illuminations. It really was an illumination for me. At last I came out of that hideous world of Taine, of Renan and the other Molochs of the nineteenth century, that penal colony, that appalling machine governed by laws that were completely inflexible and, horror of horrors, knowable and teachable .... I had the revelation of the supernatural.` [25]

Positivism, materialism, atheism—these are the deadly enemies of art, for they blind a man to the wealth and wonder of being It was from all such rude reductions of reality that William Blake asked to be delivered when he prayed, 'May God us keep/ From single vision and Newton's sleep.'[26]

For a Comte or a Marx, for a Renan or a Taine the world is a machine, a closed system. But the great artists, even when they lack explicit faith, reveal the marvel of what is, in all its transcendental richness. The lovely Muse of Poetry may not always be a Christian, but, as Gertrud von Le Fort suggested, 'in her deepest impulses, unconsciously yet irresistibly, [she is) ordered towards what is Christian and is flooded with a gentle Advent-like light.' [27]"

Footnotes:

[23] Cf. Sacrosanctum concilium, no. 112, on sacred music.

[24] CCC 2502.

[25] Jacques Rivière and Paul Claudel, Correspondance 1907-1914 (Paris, 1926), 142f. Newman said something similar about the influence of Sir Walter Scott's literary art on the Oxford Movement: he helped to 'prepare men for some closer and more practical approximation to Catholic truth' ('Prospects of the Anglican Church', in Essays and Sketches, vol. 1, new ed. [New York, 1948], 337).

[26] Letter to Thomas Butts (November 22, 1802); Selected Poetry and Prose of William Blake (New York, 1953), 420.

[27] Gertrud von Le Fort, 'Vom Wesen christlicher Dichtung', in Aufzeich-nungen und Erinnerungen (Zurich, 1958), 47.

From The Virtue of Art and the Virtue of Religion by John Saward From The Beauty of Holiness and the Holiness of Beauty: Art, Sanctity and The Truth of Catholicism

From Ignatius Insight (February 2008)