An encounter with death, Harley 2936 f.84, c.1500

The British Library, London

Death of Richard, The Pageants of Richard Beauchamp c.1485

Cotton MS Julius E IV Item number: f.26v

The British Library, London

A grave, Add. 37049 f.32v, c 15th century

The British Library, London

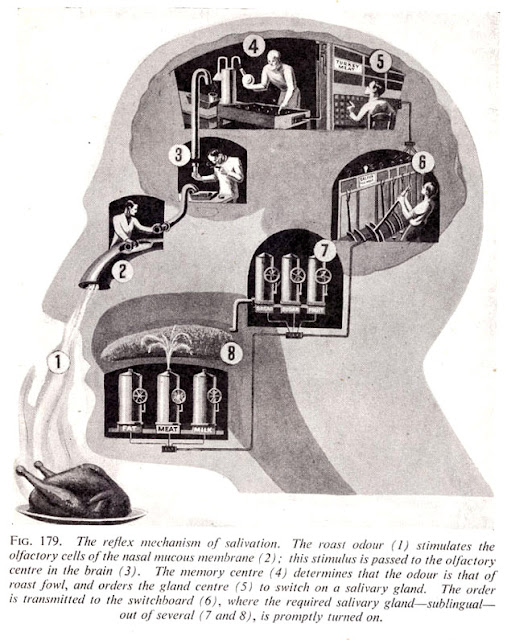

Fritz Kahn

The workings of the nervous system c. 1920

Fritz Kahn

The reflex mechanism of salivation c. 1920

In the section on History, Medieval Realms, Dr. Alixe Bovey on the British Library website writes:

"Death was at the centre of life in the Middle Ages in a way that might seem shocking to us today. With high rates of infant mortality, endemic disease, periodic famine, the constant presence of war, and the inability of medicine to deal with commonplace injuries, death was a brutal part of most people's everyday experience. As a result, attitudes towards life were very much shaped by beliefs about death: indeed, according to Christian tradition, the very purpose of life was to prepare for the afterlife by avoiding sin, performing good works, partaking the sacraments appropriately, and adhering to the Church's teachings. Time was measured out in saint's days, which commemorated the days on which the holiest men and women of Christendom had died. Easter, the holiest feast day in the Christian calendar, celebrated the resurrection of Christ from the dead. The landscape was dominated by parish churches - the centre of the medieval community - and the churchyard was the principal burial site

"

Of the "Pageants of Richard Beauchamp", the website of The British Library states:

"[It is t]hought to have been made for Anne, Countess of Warwick and daughter of Richard Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick (1382-1439), this is the only illustrated biography of a secular figure to have survived from the late Middle Ages. Richard Beauchamp was a true high-flyer, but his daughter married Richard Neville ('The Kingmaker'), who opposed Edward IV and so caused the exclusion of Anne from all her possessions after his death. It is believed that, to help recover the family's reputation and property, Anne had the 'Pageants' written, probably from an account kept by the family and possibly under the supervision of John Rous (Beauchamp's chantry priest at the Collegiate Church of St Mary's, Warwick), and the extraordinary illustrations made by a Continental artist (known as the Caxton Master) to enhance further the glorifying message.

The Caxton Master marshalled his dramatic skills and ability to create realistic figures for his depiction of Beauchamp's death. Wasted from illness, the dying man receives the last rites from a bishop, while the household is convulsed with sorrow. The lines of the figure at the foot of the bed and the bedcoverings lead the eye to the crucifix held in the centre of the picture and then to the Earl's face, signalling his religious devotion. The artist's ingeniousness comes to the fore also in the way the bed transforms into an exterior tower of the palace in which the scene takes place, further reminding the viewer of the grand status and dignity of the subject."

Of Fritz Kahn, the British Library website writes:

"Fritz Kahn's books and illustrations explored the inner machinery of the human body, using metaphors of modern industrial life. Kahn turned the brain into a complex factory with light projectors, conveyor belts, secretaries and cinema screens; he showed the journeys of blood cells as locomotives encircling the globe; and he compared bones to modern building materials such as reinforced concrete.

Kahn was writing in the 1920s, a period in of great industrial and technological change. The manufacturing industries were achieving incredibly high levels of efficiency thanks to the latest methods of production: factory assembly lines, for example, required only a simple and relatively unskilled input from factory workers. For these workers the body was like a piece of clockwork, its calculated movements acting solely as a functional cog in the social machine.

Technological advancements were bringing many other transformations to the world. A new nature was being constructed. Man could now fly, speak to people on the other side of the world, capture voices and faces that, once preserved, would later seem to be able to bring back the dead. It was an era of great excitement in which people believed that technology had the potential to create a world free from poverty and hardship - a kind of utopia in which machines would protect us from nature's moods, and would provide enough food and protection for all. In fact we were then, and are now, far from fulfilling that dream - but many believe that it is still a possibility for the future."

In December 2001, the Congregation of Divine Worship and the Discipine of the Sacraments pubished a "Directory on Popular Piety and the Liturgy: Principles and Guideines". It provided:

"259. "Hiding death and its signs" is widespread in contemporary society and prone to the difficulties arising from doctrinal and pastoral error.

Doctors, nurses, and relatives frequently believe that they have a duty to hide the fact of imminent death from the sick who, because of increasing hospitalization, almost always die outside of the home.

It has been frequently said that the great cities of the living have no place for the dead: buildings containing tiny flats cannot house a space in which to hold a vigil for the dead; traffic congestion prevents funeral corteges because they block the traffic; cemeteries, which once surrounded the local church and were truly "holy ground" and indicated the link between Christ and the dead, are now located at some distance outside of the towns and cities, since urban planning no longer includes the provision of cemeteries.

Modern society refuses to accept the "visibility of death", and hence tries to conceal its presence. In some places, recourse is even made to conserving the bodies of the dead by chemical means in an effort to prolong the appearance of life.

The Christian, who must be conscious of and familiar with the idea of death, cannot interiorly accept the phenomenon of the "intolerance of the dead", which deprives the dead of all acceptance in the city of the living. Neither can he refuse to acknowledge the signs of death, especially when intolerance and rejection encourage a flight from reality, or a materialist cosmology, devoid of hope and alien to belief in the death and resurrection of Christ.

The Christian is obliged to oppose all forms of "commercialisation of the dead", which exploit the emotions of the faithful in pursuit of unbridled and shameful commercial profit."

Is the modern attitude towards death the cause or the symptom of the hostility of some in the modern world towards the Church ? Is that why one of the most common epithets of criticism by modern critics of the Church is "medieval" ? Or is it the modern view of Man as a non-sentient "functional cog in the social machine" which denies the humanity of man which is the cause of the criticism ? Or does the reality of death fatally undermine the vision of Man as a functional cog ?

No comments:

Post a Comment