Federico Barocci

Federico Barocci

(1528/35–1612)

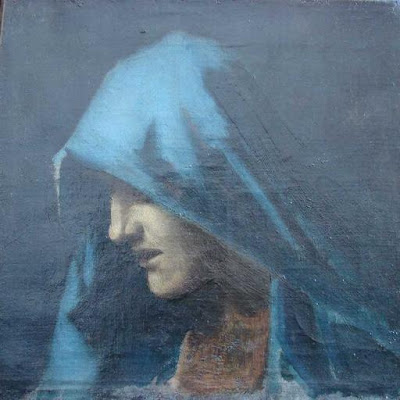

Study for the ‘Institution of the Eucharist`

Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

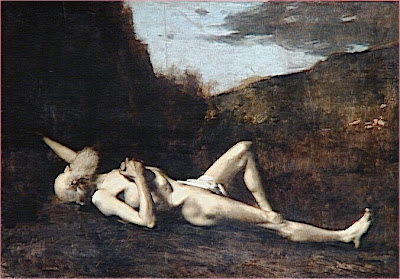

Federico Barocci

Federico Barocci

(1528/35–1612)

The Institution of the Eucharist

1608

Oil on canvas, 290 x 177 cm

Basilica di Santa Maria sopra Minerva, Rome

In 1587, Pope Clement VIII acquired the fifth chapel of the left-hand nave of the church of the Dominicans in Rome, S. Maria sopra Minerva. It was to house the tomb of his parents, Silvestro Aldobrandini and his wife Luisa Deti

In the spring of 1600 the Pope formed the plan of adorning this tomb more richly.

Clement VIII. took the liveliest interest in the decoration of the chapel to his parents. First in June, and again in October, 1602, he visited the works, which, after the death of Giacomo della Porta, were directed by Carlo Maderno.

The first visit which he made, after a serious illness, in March, 1604, was to this chapel. He personally gave directions for the placing of the statues, which he had already inspected in Cordier's studio. In December he returned once more.

Six weeks before his death in 1605, the Pope was to be seen praying in tears for an hour at his mother's tomb, which was not yet quite finished.

For the altarpiece, the Pope commissioned painter Federico Barocci. He worked on the canvas from 1603 until 1607.

At this time, the Cavaliere d'Arpino was the pope's most important artist, However Clement chose Barocci for this important and personal work.

In a letter dated 13 August 1603, Barocci said of the commission:

"Stasera uerso il tardi il Papa mi ha fatto chiamare, et quando sono stato dentro, mi ha detto ridendo, che se bene era cosa leggieri, per la quale mi hauea fatto dimandare, era pero un suo gusto et seguito, come fa fabricare una Capella qui nella Minerua in memoria de' suoi, Padre, Madre et fratelli, et desiderando, che nell'altare di essa ci fosse il quadro fatto da uallente huomo, se bene qui ce ne sono et in particulare ha Iseppino,[ the Cavaliere d'Arpino ] non dimeno si sodisfarebbe assai hauerlo di mano del Baroccio."

The Pope took a very close interest in the design and preparation of the painting.

The subject matter or theme, the Institution of the Eucharist, moved him much.

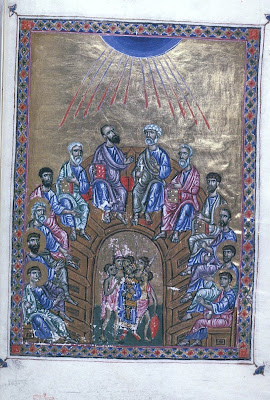

The Prayer for forty hours together before the Blessed Sacrament, in memory of the forty hours during which the sacred Body of Jesus was in the Sepulchre, began in Milan about the year 1534.

It was introduced into Rome for the first Sunday in every month by the Archconfraternity of the Most Holy Trinity of the Pilgrims (founded by St. Philip Neri in the year 1548). St Philip Neri was the private confessor of the Pope. On the death of St Philip, the successor of St Philip in the Oratory, Baronius became the confessor of the Pope.

This Prayer of the Forty Hours, practised often in one church or other at various times of the year out of devotion, was established for ever by Pope Clement VIII in 1592 for the whole course of the year, in a regular prescribed continuous succession from one church in Rome to another, commencing on the first Sunday in Advent with the chapel in the Apostolical Palace.

For reasons of historical accuracy, Clement VIII requested that the painting represent the Last Supper at night. This was notwithstanding that the picture was to be situated in a dark chapel.

The preponderance of black makes the yellow and orange of the apostles' already bright robes that much more brilliant as well as the whiteness of the Host.

In an early drawing, Barocci showed Satan accompanying Judas at his communion. According to Bellori, the pope was unhappy with the representation of the devil so near to Christ in depicting Judas' betrayal. Barocci then changed it.

As regards the posture and gestures of Christ and the placing of the Host, there is a contemporary account of the Pope`s wishes:

“vorrebe vedere la mano del Christo piu vicino all'atto del communicate e piu staccata dal petto, come fin all'hora parmi li scrivessi, l'altra che vi s'aggiunghino lumieri, che rimostrino esser stata di notte tale institutione stantissima, e pero mando l'un e l'altro....

si potesse desiderare alquanto piu aperta et espressa l'attione dell'Istitutione del S.mo Sacramento cal moto della mano piu staccata in atto di porgerlo.”

Christ holds the Host before His heart, and the shining, white disc stands out against the red of his robe. The use of scarlet reinforces the idea of the Christ's Body and Blood.

Virgin of the Rosary of Guápulo, ca. 1680

Virgin of the Rosary of Guápulo, ca. 1680